Hentai (変態 or へんたい) English /ˈhɛntaɪ/ is a word of Japanese origin which is short for (変態性欲, hentai seiyoku); a perverse sexual desire.

In Japanese, the term describes any type of perverse or bizarre sexual desire or act; it does not represent a genre of work. Internationally, hentai is a catch-all term to describe a genre of anime and manga pornography. English adopts and uses hentai as a genre of pornography by the commercial sale and marketing of explicit works under this label.

The word’s narrow Japanese-language usage and broad international usage are often incompatible. Weather Report Girl is considered yuri hentai in English usage for its depiction of lesbian sex, but in Japan it is just yuri. The definition clash also appears with the Japanese definition of yuri as any lesbian relationship, as opposed to its sexually explicit definition in English usage.

Term

Hentai (変態 or へんたい) is a kanji compound of 変 (hen; “change”, “weird”, or “strange”) and 態 (tai; “appearance” or “condition”). It also means “perversion” or “abnormality”, especially when used as an adjective.[1]:99 It is the shortened form of the phrase (変態性欲, hentai seiyoku) which means “sexual perversion”.[2] The character hen is catch-all for queerness as a peculiarity—it does not carry an explicit sexual reference.[1]:99 While the term has expanded in use to cover a range of publications including homosexual publications,[1]:107 it remains primarily a heterosexual term, as terms indicating homosexuality entered Japan as foreign words.[1]:100[2] Japanese pornographic works are often simply tagged as 18-kin (18禁, “18-prohibited”), meaning “prohibited to those not yet 18 years old”, and seijin manga (成人漫画, “adult manga”).[2] Less official terms also in use include ero anime (エロアニメ), ero manga (エロ漫画), and the English acronym AV (for “adult video”). Usage of the term hentai does not define a genre in Japan.

Hentai is defined differently in English. The Oxford Dictionary Online defines hentai as “a subgenre of the Japanese genres of manga and anime, characterized by overtly sexualized characters and sexually explicit images and plots.”[3] The origin of the word in English is unknown, but AnimeNation’s John Oppliger points to the early 1990s, when a Dirty Pair erotic doujinshi (self-published work) titled H-Bomb was released, and when many websites sold access to images culled from Japanese erotic visual novels and games.[4] The earliest English use of the term traces back to the rec.arts.anime boards; with a 1990 post concerning Happosai of Ranma ½ and the first discussion of the meaning in 1991.[5][6] A 1995 Glossary on the rec.arts.anime boards contained reference to the Japanese usage and the evolving definition of hentai as “pervert” or “perverted sex”.[7] The Anime Movie Guide, published in 1997, defines “ecchi” (エッチ etchi) as the initial sound of hentai (i.e., the name of the letter H, as pronounced in Japanese); it included that ecchi was “milder than hentai”.[8] A year later it was defined as a genre in Good Vibrations Guide to Sex.[9] At the beginning of 2000, “hentai” was listed as the 41st most popular search term of the internet, while “anime” ranked 99th.[10] The attribution has been applied retroactively to works such as Urotsukidōji, La Blue Girl, and Cool Devices. Urotsukidōji had previously been described with terms such as “Japornimation”,[11] and “erotic grotesque”,[12] prior to being identified as hentai.[13][14]

Etymology

The history of word “hentai” has its origins in science and psychology.[2] By the middle of the Meiji era, the term appeared in publications to describe unusual or abnormal traits, including paranormal abilities and psychological disorders.[2] A translation of German sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s text Psychopathia Sexualis originated the concept of “hentai seiyoku”, as a “perverse or abnormal sexual desire”.[2] Though it was popularized outside psychology, as in the case of Mori Ōgai’s 1909 novel Vita Sexualis.[2] Continued interest in “hentai seiyoku”, resulted in numerous journals and publications on sexual advice which circulated in the public, served to establish the sexual connotation of ‘hentai’ as perverse.[2] Any perverse or abnormal act could be hentai, such as committing shinjū (love suicide).[2] It was Nakamura Kokyo’s journal Abnormal Psychology which started the popular sexology boom in Japan which would see the rise of other popular journals like Sexuality and Human Nature, Sex Research and Sex.[15] Originally, Tanaka Kogai wrote articles for Abnormal Psychology, but it would be Tanaka’s own journal Modern Sexuality which would become one of the most popular sources of scholarly information about erotic and neurotic expression.[15] Modern Sexuality was created to promote fetishism, S&M, and necrophilia as a facet of modern life.[15] The ero-guro movement and depiction of perverse, abnormal and often erotic undertones were a response to interest in hentai seiyoku.[2]

Following the end of World War II, Japan took a new interest in sexualization and public sexuality.[2] Mark McLelland puts forth the observation that the term “hentai” found itself shortened to “H” and that the English pronunciation was “etchi”, referring to lewdness and which did not carry the stronger connotation of abnormality or perversion.[2] By the 1950s, the “hentai seiyoku” publications became their own genre and included fetish and homosexual topics.[2] By the 1960s, the homosexual content was dropped in favor of subjects like sadomasochism and stories of lesbianism targeted to male readers.[2] The late 1960s brought a sexual revolution which expanded and solidified the normalizing the terms identity in Japan that continues to exist today through publications such as Bessatsu Takarajima’s Hentai-san ga iku series.[2]

History

With the usage of hentai as any erotic depiction, the history of these depictions are split into its media. Japanese artwork and comics serve as the first example of hentai material, coming to represent the iconic style after the publication of Azuma Hideo’s Cybele in 1979. Japanese animation (anime) had its first hentai, in both definitions, with the 1984 release of Wonderkid’s Lolita Anime, overlooking the erotic and sexual depictions in 1969’s One Thousand and One Arabian Nights and the bare breasted Cleopatra in 1970’s Cleopatra film. Erotic games, another area of contention, has the iconic art style first depicted in sexual acts in 1985’s Tenshitachi no Gogo. The history of each medium itself, complicated based on the broad definition and usage.

Origin of erotic manga

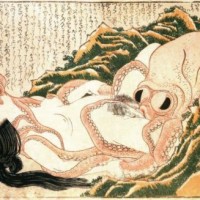

Depictions of sex and abnormal sex can be traced back through the ages, predating the term “hentai”. Shunga (春画), a Japanese term for erotic art, is thought to have and existed in some form since Heian period. From the 16th to the 19th century, Shunga works were suppressed by shoguns.[16] A well-known example is The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife which depicts a woman being pleasured by two octopi. Shunga production fell with the rise of pornographic photographs in the late 19th century.

To define erotic manga, a definition for manga is needed. While the Hokusai Manga uses the term “manga” in its title, it does not depict the story-telling aspect common to modern manga, as the images are unrelated. Osamu Tezuka, sometimes referred to as the “God of Manga”, helped define the look and form of manga itself.[17] His debut work New Treasure Island was released in 1947 as a comic book through Ikuei Publishing and sold 400,000 copies,[17] though it was the popularity of Tezuka’s Astro Boy, Metropolis, and Jungle Emperor manga that would come to define the media. This story-driven manga style is distinctly unique from comic strips like Sazae-san, and story-driven works are now dominating shoujo and shonen magazines.[17]

Mature themes in manga have existed since the 1940s, but these depictions were more realistic than the cartoon-cute characters popularized by Tezuka.[18] Early well-known “ero-gekiga” releases were Ero Mangatropa (1973), Erogenica (1975), and Alice (1977).[19]:135 The distinct shift in the style of Japanese pornographic comics from realistic to cartoon-cute characters is accredited to Azuma Hideo, “The Father of Lolicon”.[18] In 1979, he penned Cybele which offered the first commentary on unrealistic depictions of sexual acts between Tezuka-style characters. This would start a pornographic manga movement.[18] The lolicon boom of the 1980s saw the rise of magazines such as the Lemon People and Petit Apple Pie anthologies.

The publication of erotic materials in America can be traced back to at least 1990, when IANVS Publications printed its first Anime Shower Special.[20] In March 1994, Antarctic Press released Bondage Fairies, an English translation of Insect Hunter.[20]

Origin of erotic anime

Because there are fewer animation productions, most erotic works are retroactively tagged as hentai since the coining of the term in English. Hentai is typically defined as consisting of excessive nudity, graphic sexual intercourse whether or not it is perverse. The term ecchi, is typically related to fanservice, with no sexual intercourse being depicted.

Two early works escape being defined as hentai, but contain erotic themes. This is likely do to the obscurity and unfamiliarity of the works, arriving in America and fading from public focus a full twenty years before importation and surging interests coined the Americanized term of hentai. The first is the 1969 film One Thousand and One Arabian Nights which faithfully includes erotic elements of the original story.[21]:27 In 1970, Cleopatra: Queen of Sex, was the first animated film to carry an X rating, but it was mislabeled as erotica in America.[21]:104

The term typically identifies the Lolita Anime series as the first erotic anime and original video animation (OVA), it was released in 1984 by Wonder Kids. Containing 8 episodes, the series focused on underage sex and rape and including one episode containing BDSM bondage.[21]:376 Several sub-series were released in response, including a second Lolita Anime series was released by Nikkatsu.[21]:376 It has not been officially licensed or distributed outside of its original release.

The Cream Lemon franchise of works, which ran from 1984 to 2005, with a number of them entering the American market in various forms.[22] The The Brothers Grime series released by Excalibur Films contained Cream Lemon works as early as 1986.[23] However, they were not billed as anime and were introduced during the same time that the first underground distribution of erotic works began.[20]

The American release of licensed erotic anime was first attempted in 1991 by Central Park Media, with “I Give My All”, but it never occurred.[20] In December 1992, Devil Hunter Yohko was the first risque (ecchi) title was released by A.D. Vision.[20] While it contains no sexual intercourse it pushes the limits of the ecchi category with sexual dialogue, nudity and one scene in which the heroine is about to be raped.

It was Central Park Media’s 1993 release of Urotsukidoji which brought the first “hentai” film to the American viewers.[20] Often cited for creating the hentai and tentacle rape genres, it contains extreme depictions of violence and monster sex.[24] It is notable for being the first depiction of tentacle sex on screen.[12] When the movie premiered in America it was described as being “drenched in graphic scenes of perverse sex and ultra-violence”.[25]

Following this release, a wealth of pornographic content began to arrive in America. With companies such as A.D. Vision, Central Park Media and Media Blasters releasing licensed titles under various labels.[23] A.D. Vision’s label Soft Cel Pictures would release 19 titles in 1995 alone.[23] Another label, Critical Mass was created in 1996 to release an unedited edition of Violence Jack.[23] When A.D. Vision’s hentai label Soft Cel Pictures shut down in 2005, most of its titles were acquired by Critical Mass. Following the bankruptcy of Central Park Media in 2009, the licenses for all Anime 18-related products and movies were transferred to Critical Mass.[26]

Origin of erotic games

The term eroge (erotic game) literally defines any erotic game, but has become synonymous with video games depicting the artistic styles of anime and manga. The origins of eroge began in the early 1980s, while the computer industry in Japan was struggling to define a computer standard with makers like NEC, Sharp, Fujitsu competing against one another.[27] The PC98 series, despite lacking in processing power, CD drives and limited graphics came to dominate the market, with the popularity of eroge games contributing to their success.[27][28]

Due to the vague definitions of any erotic game, depending on its classification, the first erotic game is a subjective one. If the definition applies to adult themes, the first game was Softporn Adventure. Released in America in 1981 for the Apple II, Softporn Adventure was a text-based comedic game from On-Line Systems. If the definition of eroge is defined as the first graphical depictions and/or Japanese adult themes, it would be Koei’s 1982 release of Night Life.[28][29] Sexual intercourse is depicted through simple graphic outlines. Notably, Night Life was not intended to be erotic so much as an instructional guide “to support married life”. A series of “undressing” games appeared as early as 1983, such as “Strip Mahjong”. The first anime-styled erotic game was Tenshitachi no Gogo, released in 1985 by JAST. In 1988, ASCII released the first erotic role-playing game Chaos Angel.[27] In 1989, AliceSoft released the turn-based RPG Rance and ELF released Dragon Knight.[27]

In the late 1980s, eroge began to stagnate under high prices and the majority of games containing uninteresting plots and mindless sex.[27] ELF’s 1992 release of Dokyusei came as customer frustration with eroge was mounting and spawned a new genre of games called dating sims.[27] Dokyusei was unique because it had no defined plot and required the player to build a relationship with different girls in order to advance the story.[27] Each girl had their own story, but the prospect of consummating a relationship required the girl coming to love the player, there was no easy sex.[27]

The term visual novel is vague, with Japanese and English definitions classifying the genre as a type of interactive fiction game driven by narration and limited player interaction. While the term is often retroactively applied to many games, it was Leaf that coined the term with their “Leaf Visual Novel Series” (LVNS) with the 1996 release of Shizuku and Kizuato.[27] The success of these two dark eroge games would be followed by the third and final installment of the LVNS, 1997 romantic eroge To Heart.[27] Eroge visual novels took a new emotional turn with Tactics’ 1998 release One: Kagayaku Kisetsu e.[27] Key’s 1999 release of Kanon proved to be a major success and would go on to have numerous console ports, two manga series and two anime series.

Censorship

Japanese laws have impacted depictions of works since the Meiji Restoration, but these predate common definition of hentai material. Since becoming law in 1907, Article 175 of the Criminal Code of Japan forbids the publication of obscene materials. Specifically, depictions of male-female sexual intercourse and pubic hair are considered obscene, but bare genitalia is not. As censorship is required for published works, the most common representations are the blurring dots on pornographic videos and “bars” or “lights” on still images. In 1986, Toshio Maeda sought to get past censorship on depictions of sexual intercourse, by creating tentacle sex.[30] This lead to the large number of works containing sexual intercourse with monsters, demons, robots, and aliens, whose genitals look different from men. While western views attribute hentai to any explicit work, it was the product of this censorship which became not only the first titles legally imported to America and Europe, but the first successful ones. While uncut for American release, the United Kingdom’s release of Urotsukidoji removed many scenes of the violence and tentacle rape scenes.[31]

It was also because of this law that the artists began to depict the characters with a minimum of anatomical details and without pubic hair, by law, prior to 1991. Part of the ban was lifted when Nagisa Oshima prevailed over the obscenity charges at his trial for his film In the Realm of the Senses.[32] Though not enforced, it did not apply to anime and manga as they were not deemed artistic exceptions.[18] Though alterations of material or censorship and even banning of works are common. The U.S. release of the La Blue Girl altered the age of the heroine from 16 to 18 and removed sex scenes with a dwarf ninja named Nin-nin, and removed the Japanese censoring blurring dots.[21] La Blue Girl was outright rejected by UK censors who refused to classify it and prohibited its distribution.[21][33]

Demographics

As a medium, the most popular consumer are men. Eroge games in particular combine three favored media, cartoons, pornography and gaming into an experience. The hentai genre engages a wide audience that expands yearly, with that audience desiring better quality and storylines, or works which push the creative envelope.[34] The unusual and extreme depictions in hentai is not about perversion so much as it is an example of the profit-oriented industry.[35] Anime depicting normal sexual situations enjoy less market success than those that break social norms, such as sex at schools or bondage.[35]

According to Dr. Megha Hazuria Gorem, a clinical psychologist, “Because toons are a kind of final fantasy, you can make the person look the way you want him or her to look. Every fetish can be fulfilled.”[36] Dr. Narayan Reddy, a sexologist, commented on the eroge games, “Animators make new games because there is a demand for them, and because they depict things that the gamers do not have the courage to do in real life, or that might just be illegal, these games are an outlet for suppressed desire.”[36]

Classification

The hentai genre can be divided into numerous subgenres, the broadest of which encompasses heterosexual and homosexual acts. Hentai that features mainly heterosexual interactions occur in both male-targeted (ero) and female-targeted (“ladies’ comics”) form. Those that feature mainly homosexual interactions are known as yaoi (male-male) and yuri (female-female). Both yaoi and, to a lesser extent, yuri are generally aimed at members of the opposite sex from the persons depicted. While yaoi and yuri are not always explicit, the pornographic history and association remains.[37] Yaoi’s pornographic usage has remained strong in textual form through fanfiction.[38] The definition of yuri has begun to be replaced by the broader definitions of “lesbian-themed animation or comics”.[39]

Hentai is perceived as “dwelling” on sexual fetishes.[40] These include dozens of fetish and paraphilia related subgenres, which can be further classified with additional terms, such as heterosexual or homosexual types.

Many works are focused on depicting the mundane and the impossible across every conceivable act and situation no matter how fantastical. The largest subgenre of hentai is futanari (hermaphroditism), which most often features a female with a penis or penis-like appendage in place of, or in addition to normal female genitals.[41] Futanari characters are primarily depicted as having sex with other women and will almost always be submissive with a male; exceptions include Yonekura Kengo’s work, which features female empowerment and domination over males.[41]

References

1.^ Jump up to: a b c d Livia, Anna; Kira, Hall (1997). “Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender, and Sexuality”. Oxford University Press.

2.^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o McLelland, Mark (January 2006). “A Short History of ‘Hentai'”. Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context (12).

3.Jump up ^ “hentai”. Oxford Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press.

4.Jump up ^ Oppliger, John. “Ask John: How Did the Word ‘Hentai’ Get Adopted Into English?”. AnimeNation.

5.Jump up ^ Newton, Mark (8 February 1990). “Ranma 1/2”.

6.Jump up ^ “Some little questions”. 12 April 1991.

7.Jump up ^ Sinclair, Iain (17 March 1995). “rec.arts.manga Glossary”.

8.Jump up ^ McCarthy, Helen (27 October 1997). The Anime Movie Guide. Overlook Press. p. 1987.

9.Jump up ^ Winks, Cathy (7 November 1998). Good Vibrations Guide to Sex: The Most Complete Sex Manual Ever Written. Cleis Press.

10.Jump up ^ “Forget Sex and Drugs. Surfers Are Searching for Rock’n’roll as the Net Finally Grows Up”. The Independent (London). 18 January 2000.

11.Jump up ^ Marin, Cheech. “Holy Akira! It’s Aeon Flux”. Newsweek 107 (7).

12.^ Jump up to: a b Harrington, Richard (26 April 1993). “Movies; ‘Overfiend’: Cyber Sadism”. The Washington Post.

13.Jump up ^ “Urotsukidoji I: Legend of the Overfiend (1989)”. The New York Times.

14.Jump up ^ Span, Paula (15 May 1997). “Cross-Cultural Cartoon Cult; Japan’s Animated Futuristic Features Move From College Clubs to Video Stores”. The Washington Post.

15.^ Jump up to: a b c Driscoll, Mark (13 July 2010). “Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan’s Imperialism, 1895–1945”. Duke University Press. pp. 140–160.

16.Jump up ^ Bowman, John (2000). “Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture”. Columbia University Press.

17.^ Jump up to: a b c “A History of Manga”.

18.^ Jump up to: a b c d Galbraith, Patrick (2011). “Lolicon: The Reality of ‘Virtual Child Pornography’ in Japan”. Image & Narrative, Vol 12, No1. The University of Tokyo.

19.Jump up ^ Gravett, Paul (2004). Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics. Laurence King Publishing.

20.^ Jump up to: a b c d e f “Ask John: How Did Hentai Become Popular in America?”. Anime nation.

21.^ Jump up to: a b c d e f The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917. Revised and Expanded Edition. Stone Bridge Press. 2006.

22.Jump up ^ “Ask John: How Much Cream Lemon is There?”. animenation.net.

23.^ Jump up to: a b c d “The Anime “Porn” Market”. awn.com.

24.Jump up ^ “Not Fit To Fap To: Urotsukidoji: Birth of the Overfiend (NSFW)”. Metanorn.

25.Jump up ^ Richard Harrington. “Movies; `Overfiend’: Cyber Sadism.” The Washington Post. Washingtonpost Newsweek Interactive. 1993.

26.Jump up ^ “Central Park Media’s Licenses Offered by Liquidator”. Animenewsnetwork.com. 8 June 2009.

27.^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Todome, Satoshi. “A History of Eroge”.

28.^ Jump up to: a b “Hardcore gaming 101: Japanese computers”. Hardcoregaming101.

29.Jump up ^ Jones, Matthew T. (December 2005). “The Impact of Telepresence on Cultural Transmission through Bishoujo Games” (PDF). PsychNology Journal 3.

30.Jump up ^ “Hentai Comics”. Maeda, Toshio.

31.Jump up ^ “Urotsukidoji III – The Return of the Overfiend”. Move Censorship.com.

32.Jump up ^ Alexander, James. “Obscenity, Pornography, and the Law in Japan: Reconsidering Oshima’s In the Realm of the Senses”.

33.Jump up ^ bbfc (30 December 1996). “LA BLUE GIRL Rejected by the BBFC”.

34.Jump up ^ Bennett, Dan. “Anime erotica potential growing strong.(Animated erotica).” Video Store. Questex Media Group, Inc. 2004.

35.^ Jump up to: a b “Bizarre sex sells in weird world of manga.” New Zealand Herald (Auckland, New Zealand). Independent Print Ltd. 2011.

36.^ Jump up to: a b “Oooh Game Boy.” Hindustan Times (New Delhi, India). McClatchy-Tribune Information Services. 2007.

37.Jump up ^ McHarry, Mark (November 2003). “Yaoi: Redrawing Male Love”. The Guide.

38.Jump up ^ Kee, Tan Bee. “Rewriting Gender and Sexuality in English-Language Yaoi Fanfiction.” Boys’ Love Manga: Essays on the Sexual Ambiguity and Cross-Cultural Fandom of the Genre (2010): 126.

39.Jump up ^ “Yuricon – What is Yuricon?”. Yuricon. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

40.Jump up ^ “Peek-a-boo, I See You: Watching Japanese Hard-core Animation”. Springerlink.com.

41.^ Jump up to: a b “Ask John: What is Futanari and Why is it Popular?”. Anime Nation.